By Catherine Reagor & Megan Taros | Arizona Republic

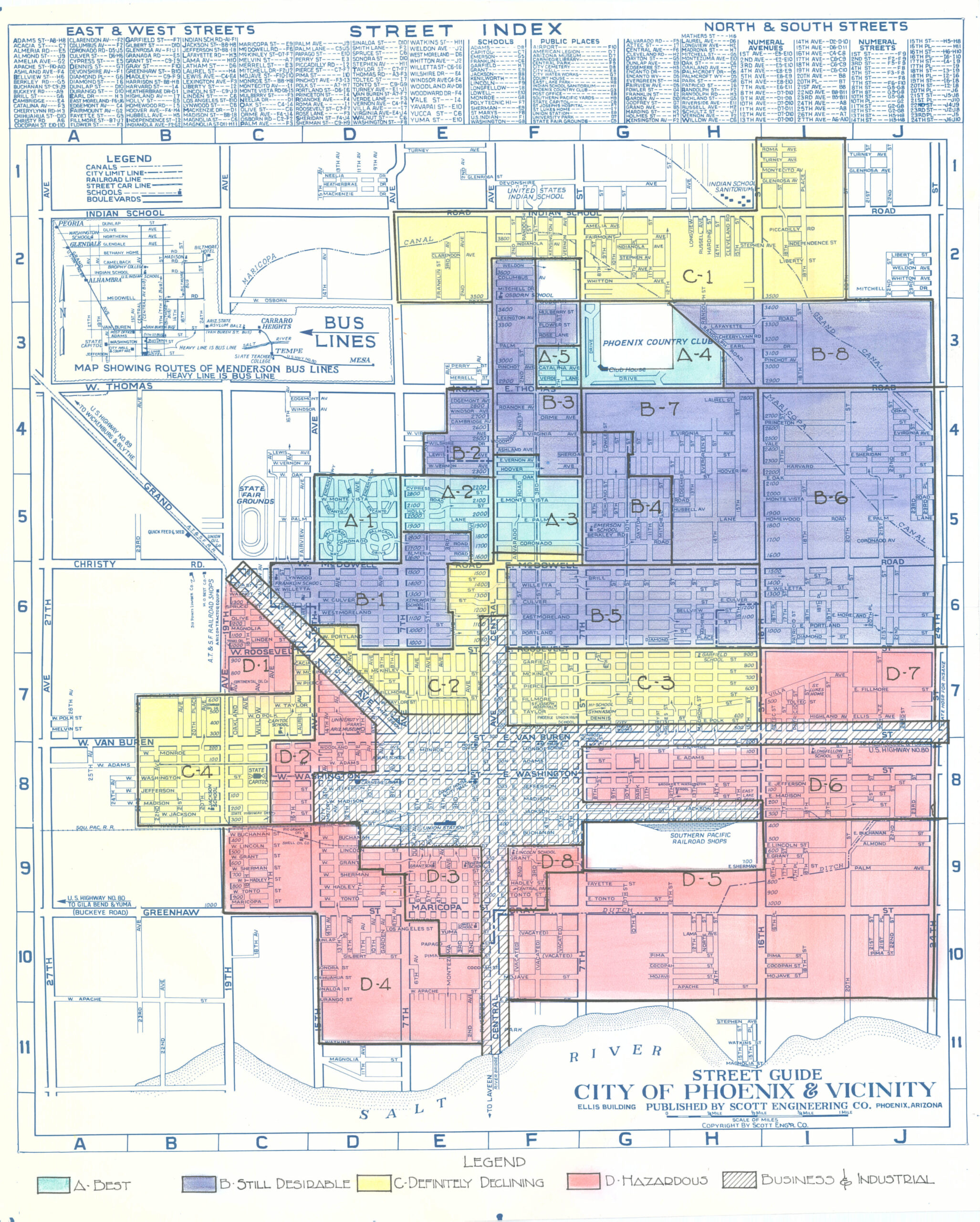

Housing discrimination, including disastrous government-supported redlining is hurting south Phoenix neighborhoods more than 50 years after it was struck down as illegal and predatory.

Neighborhoods across south Phoenix still have low homeownership rates among Black and Latino people after areas south and east of downtown were redlined by the federal government in the 1930s.

That designation, the only one given to an area in Arizona, meant banks wouldn’t lend to people trying to buy homes there.

That government action, as well as deed restrictions on where people of color could buy homes and other unfair practices, pushed many Black and Latino families south of downtown Phoenix and across the Salt River into substandard housing and neighborhoods with no sidewalks, public lighting or trees.

And by keeping the area’s residents from getting mortgages to buy homes for so long, the discriminatory polices kept many families from building the home equity that translates to savings and wealth.

Many parts of south Phoenix are now being revitalized with new housing and shopping developments and investment from the extension of light rail.

But the area, which saw some of the highest foreclosure rates during the Great Recession, is now seeing some of the biggest jumps in rents and home prices in the Valley.

South Phoenix’s real estate boom is shutting the door on many of the area’s longtime residents who can’t afford to live there now.

Housing advocates say the city hasn’t done enough to help them rebound.

Historical practices kept homeowner rates lower

Discriminatory housing practices started in Phoenix more than a century ago.

ASU’s Morrison Institute for Public Policy documents the history of Maricopa County and five other areas across the state affected by predatory housing policies in its report A Brief History of Housing Policy and Discrimination in Arizona.

“Present-day factors that determine where and how one can buy a home are influenced by historical public policy choices,” according to the report. “Past policies encouraged white homeownership, protected white people from economic downfall, and created segregation between white people and people of color.”

Although some policies have tried to reverse these practices and racial integration has drastically increased, the past still weighs on the present housing landscape of Arizona, the report found.

The impact of unfair housing policies can be seen in Arizona’s homeownership rates.

Black homeownership has dropped in Arizona during the past 50 years, despite approval of the Fair Housing Act that made discrimination illegal in 1968.

Latino homeownership in Arizona fell during the 2008 housing crash and hasn’t rebounded, reports Morrison.

In 1970, about 66% of white households in Arizona owned a home, and about 49% of Black households owned a home, according to census data.

By 1990, white homeownership had slightly increased to 67% of households, while Black homeownership decreased to 41% of households.

During the housing boom, many Black and Latino people were targeted with predatory subprime loans. In 2006, 53% of all U.S. Black homebuyers and 47% of Latino homebuyers were using a subprime loan to buy or refinance. That compares with 26% of white homebuyers getting subprime loans.

In Arizona, which led the nation for foreclosures during much of the crash, subprime mortgages accounted for the majority of homes taken back my lenders. South and west Phoenix neighborhoods were hardest hit by the foreclosure crisis.

The latest census data shows in Arizona that white homeownership was 71.1% in 2019. The Latino homeownership rate was 53.9%, and Black homeownership was 34.6%.

Most neighborhoods in south Phoenix have even lower rates of Black and Latino homeowners.

Read more (subscriber content)

Some stories may only appear as partial reprints because of publisher restrictions.